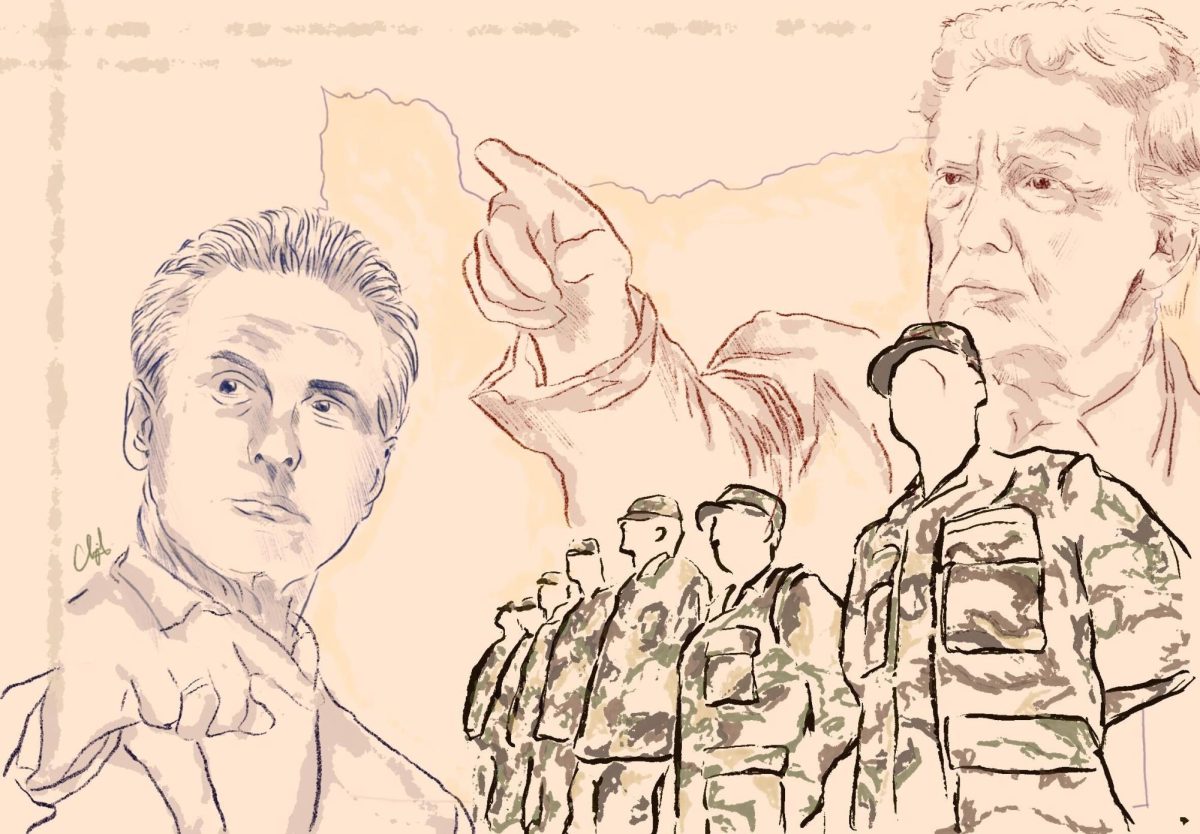

Last year’s 32-percent fee hike drew a huge reaction across California: Millions turned out for the March 4 Day of Action, in addition to those that made their voices heard at the November UC Board of Regents meeting at UCLA. The outrage was everywhere, and UC President Mark G. Yudof spent most of the year justifying the move. But it looks like he didn’t learn his lesson, and — with the Regents voting on his proposed 8-percent fee increase at their meeting at UC San Francisco this week — we’ll be the ones to pay the price.

The Regents know that when it comes down to it, students have no leverage. The only way for us to truly make an impact is to boycott the UC and deprive them of 181,000 sources of revenue. And while we’re not about to drop out, pretty soon we won’t be able to afford any other option.

This second fee increase is frustrating, it’s demoralizing, and it makes us feel like we’re part of a system that only cares about our ability to open our wallets. Even more depressing is the fact that in the history of the UC system, fee hikes have been implemented since its conception, but in 142 years tuition has never once decreased.

The UC system was founded on the principle that it would provide the most accessible public and high-quality education to students in the state of California. But the more the system turns away from state funding and relies on our pocketbooks, the less accessible it becomes to every Californian.

The sad thing is, there is no win-win here; when system is strapped for cash, it only has two real options. It can raise fees, or it can sacrifice the quality of education by increasing class sizes, adding furlough days and reducing the selection of classes. As much as it kills us, we have to cough up if we want to keep attending our university.

More Out-of-State Students

The second, though less controversial, topic of discussion at the Regents meeting is the UC Commission on the Future recommendation that the campuses increase the number of out-of-state students. The Commission analyzed enrollment numbers from the 2008-09 school year and found that 6 percent — around 10,000 — of UC undergraduates are from outside California. With this in mind, the commission asked for this number to rise to 10 percent, or 18,000 students. These extra 8,000 kids will add to the university’s endowment to the tune of $91 million.

Opponents bring up important matters of diversity — accepting more affluent students, capable of paying the $23,000 tuition price tag, would be cutting out the in-state students that need the lowered cost of public education to begin with. But the fact remains that each out-of-state student pays roughly twice the $11,124 the other 94 percent of undergraduates pay. During this UC budget crisis, outsourcing the financial burden of higher tuition to those who voluntarily pay it is better than levying it on the rest of the students — many of whom can’t afford it. An 8 percent fee increase, coupled with the expanded financial aid, will affect 45 percent of current UCSD undergraduates; that’s 81,000 students who would be forced to pay more, in comparison to 18,000 who are willing and able to shell out the money for a UCSD diploma.

Pricier Employee Pensions

In November of 1990 — before some of its current students were even born — the UC system found itself with a surplus in its pension plan. At that point, both the university and its employees stopped contributing money, choosing instead to ride on the state’s contribution, investments and the interest on the funds that already existed. Now, 20 years, some poor financial choices and an economic crisis later, pension payments are back and on the rise. But if those workers are going to have anything to support them when they’re old and grey, these changes need to happen.

One increase was passed in September, which said that, as of July 2012, employees will contribute 5 percent of their paychecks to a retirement plan, while the university will pay 10 percent. The discussion in November centers around future employees — specifically, those hired after July 2013 — who would have a cap placed on their benefits, an increased minimum age of retirement, and contribute 5.1 percent of their paychecks to the current employees’ 5 percent.

UC employees haven’t contributed to this fund for almost two decades (payments started back up again at 3 percent in spring of this year), and now they’re facing $6.3 million in liabilities; if the program doesn’t undergo structural changes now, there will be no pension fund at all in a few years.

The UCLA website says that “One of the most attractive features of UC employment is the University of California Retirement Plan” — even if that means a smaller paycheck and a higher retirement age, it’s worth it for the chance at a strong program that will draw new hires.

It does look like a paycut; within the span of a few months, 3 percent of employees’ paychecks have virtually vanished, to be followed by another 2 percent within the next couple years. But the university is upping its contribution as well. This isn’t a burden shouldered by employees alone, but by the system overall, which should ultimately benefit the worker.

The smaller paycheck now will come back in the form of post-retirement financial security, including medical benefits and the option of a lump sum cash out — it’s not like this money is vanishing into thin air. If it comes down to a collapsing retirement fund or paying a little more out of pocket now to support yourself 20 years down the road, then there’s no contest.