Editor’s note: Interviewees were granted anonymity due to concerns over retaliation and safety.

In November of 2022, in the largest university strike in American history, 48,000 academic workers across the UC system walked off the job to demand higher wages and better benefits. The strike was led by the United Auto Workers union, which represents graduate teaching assistants, undergraduate instructional assistants, postdoctoral researchers, and other academic student employees. After 39 days on strike, the union reached an agreement with the UC system for a new contract that raised wages and added new healthcare and childcare benefits.

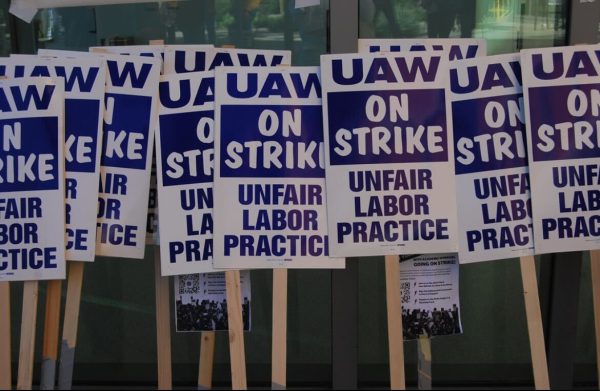

Now, a year and a half later, all eyes are again on the UAW as a new strike is brewing. In response to the UC system’s crackdown on pro-Palestine protests on multiple UC campuses, UAW members passed a strike authorization on May 15. The vote, which passed with an overwhelming majority of 79% in favor, did not call an immediate system-wide strike as it did in 2022. Rather, it gave union locals at individual campuses permission to walk off the job at a time of their own choosing.

This concept was inspired by the “stand up strike” model that the UAW deployed to great effect against three major auto manufacturers in 2023. The strike aims to maximize disruption by having different units go on strike at different times with little warning to employers. Academic workers at three UC campuses — Santa Cruz, Los Angeles, and Davis — have “stood up” and walked off the job so far. UC San Diego’s academic workers will be joining the strike on Monday, June 3.

While the chance of a new strike has monopolized the attention of students and faculty, the effects of the 2022 strike still linger. UCSD’s biology department is a prime example; administrators reacted to the new contract by eliminating the great majority of graduate TA positions in the department. This led to the cancellation of all in-person discussion sections, which were previously an integral part of many biology courses.

The elimination of in-person discussions, as well as most TA positions, brought about drastic changes to how UCSD’s biology courses are run and forced faculty, academic workers, and students to scramble to adapt.

The changes took effect at the beginning of this academic year. Instead of smaller in-person sections led by a mix of graduate TAs and undergraduate IAs, students in biology classes crowded into massive online discussion sections which often included hundreds of students on a single Zoom call. In these online sections, undergraduate IAs and the few remaining TAs have attempted to answer questions and work through problems with hundreds of students at a time.

With the end of the academic year approaching, biology department faculty, academic workers, and students are taking stock of how this year’s experiment has worked — and, by and large, they do not like the results.

A professor in the biology department, who has been granted anonymity due to concerns over retaliation, has been sharply critical of these changes since they were first implemented.

“It’s a pure economic thing,” the professor said, arguing that the administration eliminated TAs and discussion sections solely to save money. The professor added that university administrations are increasingly putting monetary concerns above academics.

“It’s a detriment to teachers, students, and education, period,” he said.

The professor noted that this is a continuation of a trend that had been ongoing for years, in which administrators have gradually forced professors to hire less paid academic student employees and shift more of the workload onto first-time undergraduate IAs, who are not paid for their work. When faced with the prospect of paying their student employees more in the wake of the 2022 strike, biology department administrators took even more drastic measures.

The professor expressed his frustration with what he described as the unaccountable nature of the decision-making process and the disconnect between university administration on the one hand and students and faculty on the other. He said that faculty were not consulted before the decision was made and that administrators stonewalled their attempts to find out who exactly was responsible for the changes.

“When you’re trying to find out who’s making these decisions, they don’t have names. Give me the names, show me the budgets — but they won’t even give you the names and authority of the people who made these decisions,” he said.

A master’s student working as a graduate TA, who was granted anonymity, similarly stated that the reasons for the change were not transparent.

“It was just, ‘It is.’ They never provided us with any kind of explanation for why it happened,” the TA reported.

According to the TA, the change in course structure has had a noticeable impact on the students in these classes.

“I will say participation in discussion has dramatically decreased,” the TA said. “Now I only get maybe 80 students coming to [virtual] discussion, and that’s out of a 400 person class — so, less than a fourth of them. Maybe that’s also affecting their grades a little bit, because I know people say discussions really helped them understand the material more — but if you’re not coming, you can’t digest it as fully.”

The TA also noted that she moved her office hours from online to in-person in an attempt to create some kind of face-to-face interaction with her students, which the Zoom format does not allow for.

An undergraduate IA also said that the new format has greatly diminished the connection between students and the teaching staff.

“I feel like I would’ve been able to build a stronger relationship with the students in the class, and build their confidence in course material more effectively [if sections were in-person],” she said.

The IA reported that, since most of her interaction with the students is through the chat function on a crowded Zoom call, students are more reluctant to attend office hours or ask questions of an IA they have never interacted with in-person.

“Their will to try to reach out to us is kind of diminished by that,” the IA added. “I don’t feel like I have the connection that I could’ve had with the students in the class.”

Students have also expressed that the changes are unfair to them.

“I feel like we all came in with the expectation that we were going to get the learning experience that we originally signed up for,” said Neha Jensen, a junior in Seventh College majoring in human biology. “For what we’re paying, we should be getting a more interactive hands-on experience, especially as a very STEM-heavy school.”

Professors forced to adapt to the decisions of a faceless university bureaucracy, TAs losing their jobs, a major disconnect between students and teaching staff, students having a harder time learning and getting the help they need: these, according to the students and staff interviewed for this article, are the effects of last year’s post-strike policy changes — changes in which faculty and students had no say, and for which it seems that no one can be held accountable.

The professor quoted above expressed his hope that there will, at some point, be a reckoning with the way in which these changes have impacted students, faculty, and student employees.

“The way they win is that eventually everyone just gives up and accepts it, and piece by piece by piece they can do more of what they want,” he said. “To have a school like UCSD, which is a premier research institution, doing something like this to its students — it’s unforgivable.”