On Dec. 12, UAW Local 5810 held an emergency rally to protest the mistreatment and layoffs of several international postdoctoral workers. Since then, though some individuals’ situations have improved, many have only become more severe, particularly in the case of Suresh Madheswaran. The union plans to hold a rally on Jan. 17 in front of Moores Cancer Center to call for immediate action from UC San Diego to protect Madheswaran and demand institutional improvement in the treatment of international workers.

Madheswaran, a postdoc with research interests in tumor immunology, moved from India to work at UCSD after being promised a long-term appointment under his principal investigator. Though recruited under a one-year contract at first, Madheswaran’s appointment was extended until Jan. 2025 within three months of joining due to positive performance reviews.

On Nov. 13, seven days after the birth of his newborn infant, Madheswaran received an email from his PI to join a Zoom where she informed him that he was “released” from his position with no warning, effective immediately.

In the weeks leading up to and after the birth of his child, Madheswaran had contacted his PI several times to discuss his paternity leave and the security of his position once the leave lapsed.

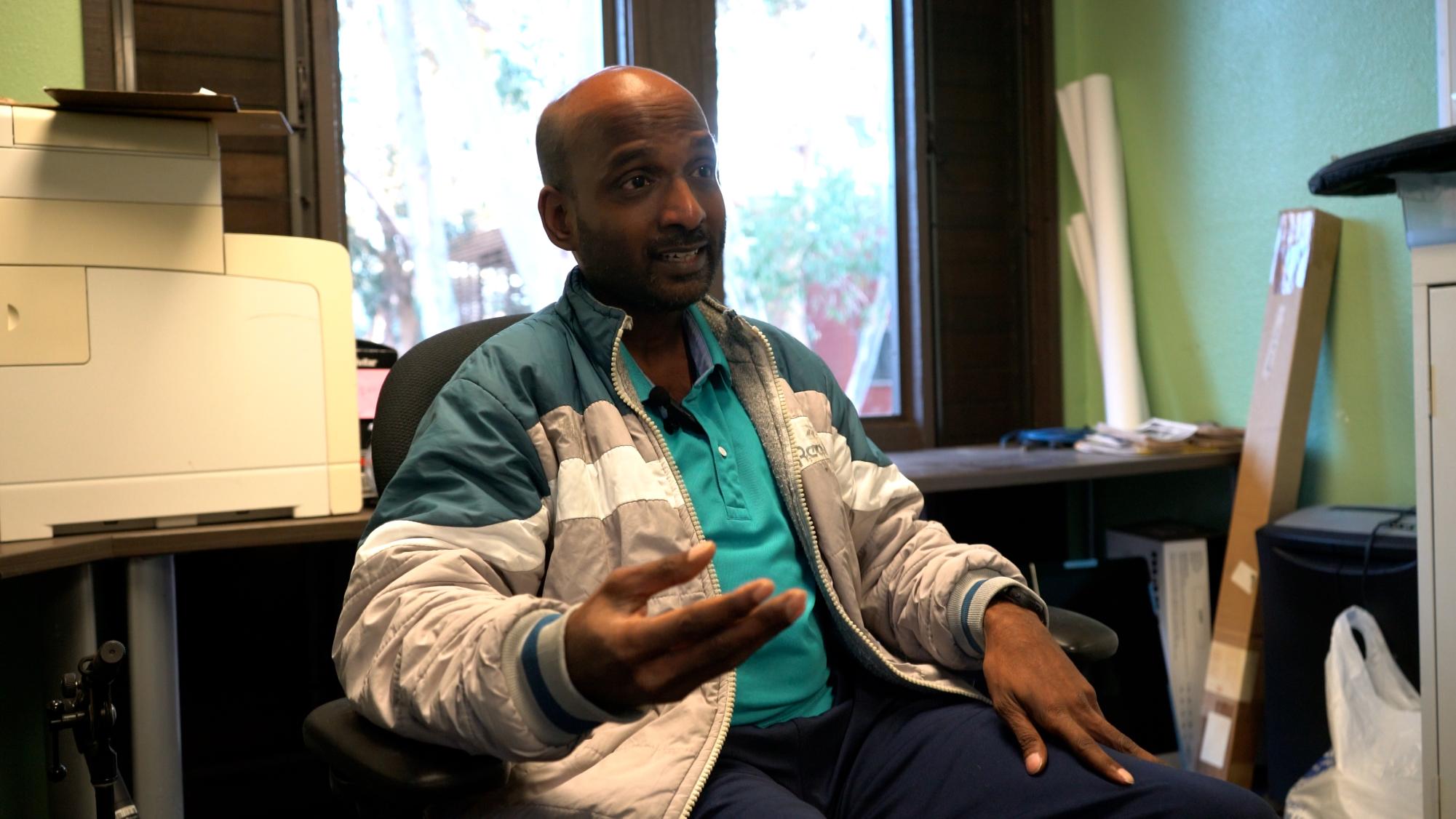

“My PI is well aware of all these things — when my baby will be delivered, when is my wife’s pregnancy, she knows everything. Despite of that, she released me from the postdoc position,” Madheswaran said.

On Nov. 3, after taking his wife to the hospital, Madheswaran asked his PI what the procedure for taking paternity leave would be. After receiving no response, he contacted UCSD Health Human Resources instead. Two days later, his baby was born. His PI responded with the Zoom call only after he informed her that he had been approved for eight weeks of paid paternity leave and four weeks of paid personal leave.

The Zoom call served as the beginning of Madheswaran’s one month of notice prior to the termination of his employment, after which he would enter his one-month grace period before he must leave the country. He was offered no further communication, explanation, or support. He would be separated from his wife, who is currently battling postpartum depression, and his newborn baby, whose immune and nervous systems are developing and cannot travel. Since this situation has unfolded, Madheswaran has had to begin taking medication to combat high levels of anxiety due to this uncertainty.

“They can’t just throw [us] out like wastepaper. We are humans. We have family members, we have emotions, we have feelings, we have a dream,” Madheswaran said. “I know this is unfair. This is totally unfair. I didn’t expect this [from a] big university [like] UCSD. When I was landing up here, I was thinking that UCSD gives equal rights to everyone, but it’s like one man’s decision.”

In order to come to the U.S., Madheswaran said he had to use up his life savings.

“[Many international workers] come from poor backgrounds. India is a developing nation, and in India, a flight ticket is very huge money,” Madheswaran explained. “I didn’t get any savings in my life. So after my PhD, whatever [funds] I have from my wife, I’m using [it all] to get a [plane ticket to the US] for me and my wife and one-month’s living expenses.”

For international workers like Madheswaran, their contract with UCSD is more than a simple job appointment: it is the promise of a long-term future to research and settle in the US and a decision to entirely uproot their families.

“If they [aren’t] able to stick with the contract, then what is the point of giving the contract? They signed it for two years. That is like a promise that you will be able to work here for two years, and they are providing the promise. But if they don’t like us, they just throw [us] out,” Madheswaran said. “Sometimes, I may be wrong. Sometimes, my team may be wrong. But, at least they should give me a warning, right? They didn’t give me warning and they didn’t even say anything [to me]. Just like that, they throw me out. And too, during my paternity leave.”

A contract violation of this severity means that Madheswaran and his family are at risk of losing everything, not just the primary income and health insurance afforded by his position.

“Imagine if I want to go back [to India] without knowing where I’ll go,” he said. “I don’t have a job. I don’t have a place to stay.”

Madheswaran speculated on several reasons for his release, including an unresolved conflict about the direction of the project. Though the official reason for his release was lack of funding, Madheswaran believes that this would not make sense with the sudden nature of his release.

“UCSD is not interfering in these issues. They are just thinking that this is not that important, this is a PI and postdoc issue. No. This is a PI, postdoc, and UCSD issue, because UCSD is also giving room and space for my PI’s lab,” Madheswaran said. “If I am liable, I’m ready to take whatever and leave. But there’s no investigation from UCSD … There is no transparency. There is no further investigation. There [are] no team members apart from my PI and me to discuss what happened.”

Even if the funding was the true reason for Madheswaran’s release, doing so during his paternity leave is a clear violation unto him and his family. Madheswaran said he should have at least been told either well before or after his paternity leave in order to give him adequate time to secure his visa with a new employer or at the very least, to get a passport for his newborn baby.

“In that case, after eight weeks [of paternity leave], they should be giving a one month notice period and one month grace period, so at least this time period should be enough to look for some alternative position,” Madheswaran explained. “But, when they release me during the [time of paternity leave and right before the holidays], how do I get a response?”

Traditionally, institutions are required to provide one month’s notice if they release a worker before the grace period begins, allowing sufficient time for the worker to either find a new job appointment in the U.S. or to make arrangements to leave the country, as once they leave, they are unable to return for two years. Because Madheswaran was released during his leave, the time he has to care for his family is rapidly shrinking.

As of Jan. 7, only a couple of days after workers returned from the holidays, Madheswaran has already entered his grace period. He currently has until early February before he overstays his visa, but if UCSD intervenes, this time could substantially increase.

“I’m looking for an opening position, but I need some time,” he said. “If they had not violated my paternity leave, I would still have some time. That would give me some hope.”

Despite some positive responses from a few possible appointments, the earliest most institutions are willing to make hiring decisions is the middle of March, a reasonable waiting time that was taken from Madheswaran when UCSD violated his contract.

The union is working with Madheswaran to demand UCSD honor at least a six to eight-week extension before his grace period via re-appointment or another protection. The focus of the Jan. 17 rally is to demand just treatment for Madheswaran and other international postdocs affected like him, now and forever.

“We’re appalled at how UCSD has treated Suresh, and we want them to know that academic workers at UC stand behind him 100%,” said Chapin Cavender, a union leader and postdoctoral fellow in Pharmaceutical Sciences. “We don’t understand why UCSD is so much more vindictive than other UC campuses, and we won’t stop coming back until he and other international postdocs are treated fairly.”

“At least, what belongs to me, give me that,” Madheswaran said. “Why do you break the rules? You don’t follow the rules, then why do you [make them]? Why do you make a two-year contract, why do you make this document, why do you say there is paternity leave for eight weeks? If you give all this information, you must follow that. And if you’re not following that, and no one is ready to listen, then what is the point of the big institution of UCSD?”