On May 21, members of the UC San Diego writing community sent a statement to UCSD Chancellors and Provosts responding to the May 6 raid on the Gaza Solidarity Encampment. The statement focuses on the violence done with words relating to the raid and other protest actions.

The letter was initially emailed to Chancellor Khosla, Executive Vice Chancellor Simmons, Vice Chancellor Petitt, Vice Chancellor Satterlund, Associate Chancellor Gattas, Associate Chancellor Kish, Senior Associate Vice Chancellor Continetti, Professor Hildebrand, Provost Yu, Provost Yang, Provost Carver, Provost Abrajano, Provost Evans, Provost Chilukuri, Provost Antonovics, and Provost Booker. At the time, nine writing community members had signed the letter. They have not received any responses.

As of June 4, the statement has over 50 signatories, having been continuously circulating amongst the writing instructors at UCSD and the broader San Diego community. The letter is still collecting signatures via a form on the bottom of their Google site. They invite “all those whose conscience calls to sign” to join the signatories.

The full statement submitted reads as follows:

Words matter. Words can reveal hidden depths or conceal them. Words can bring people together or divide. They can reconcile people or incite violence. We, the undersigned, know this. We know this because we are writing teachers. We work with words.

We also know that silence in times of crisis speaks louder than words. This is why we write now. We cannot remain silent.

On May 6, 2024, our campus community experienced a crisis: violence unleashed against peaceful protestors, arrests and suspensions of peaceful protestors.

This violence was not initiated by students. It was lit by words—the Chancellor’s words. As writing teachers, we write to condemn those words. This writing crossed a line, ironically the very line the administration purports to protect: the line separating speech that can be spoken or written freely and speech that cannot be uttered because it endangers the public.

Words that criminalize

The Chancellor’s email written and delivered on May 5, 2024, equated to yelling fire on a fireless campus.

In that email, the Chancellor writes in cold legalistic language that bleeds out the protestors’ humanity and turns them into criminals:

“On May 1, 2024, campus community members and non-affiliates established an illegal encampment near Library Walk.”

Notice how the wording casts a shadow on concerned members of the public who stood with the students at a public university. They become “non-affiliates,” lumped into the category of law breakers.

The writer then portrays the administration as benevolent, noting their frustrated attempts to meet with students:

“We have been met with shifting liaisons and claims that the encampment has no organized leadership with whom to reach binding agreements.”

Some of us chose to be faculty witnesses to the encampment. Tested against our witness and multiple other sources, this claim is patently false. Student leaders were observing campuses like UC Riverside and seeing how they could follow suit with a strategy that ended in acknowledgement of their terms and peaceful resolution. At the same time, on May 10, according to the Chair of the Academic Senate, faculty members were making urgent requests to the administration that they meet with students in person. The evening before the armed intrusion by police, students and faculty were prepared to open a dialogue. Their requests were met with silence.

Finally, the writer turns to the dangers of the encampment.

“The encampment poses serious safety and security hazards to those inside and outside the encampment area. In the last week, the encampment has limited free movement on campus, created a checkpoint for entry into the camp, and denied access to the fire marshal and health inspectors. As time passes, the threat and potential for violent clashes increases. The presence of a significant number of non-affiliates in the encampment heightens these concerns.”

Note the actor posing the hazard: the encampment. To blame these encampments for violence is, to quote Dr. King, “like condemning a robbed man because his possession of money precipitated the evil act of robbery.” As we saw with UCLA, the threat of violence came from counter-protestors attacking the encampment while police stood by.

As for the camp itself, we saw a different space than the one described. It was safe, secure, and joyous. The students had areas for food and prayer. The grounds were cleaned. The nights were tranquil and reflective. Movement along Library Walk flowed. When the walkway was momentarily blocked, it was for song or dance. There were no checkpoints other than watchful administrative personnel.

Words on the wrong side of history

The Chancellor invokes a campus policy prohibiting encampments to show the law is on his side. From our perspective, the more enshrined democratic rights of free speech and free assembly far eclipse that policy.

If it were determined that the protestors broke a law, we might remind the Khosla administration of history: Civil rights protestors broke the law when they marched across the Edmund Pettus Bridge. That march was an illegal assembly that was characterized as endangering public peace.

The sheriff in Selma could have used his words to restrain his policemen. He could have let that march continue peacefully. Instead, he said, “Go!” To protect public peace, he ordered violence. To uphold the law, he unleashed clubs and whips. Chancellor Khosla’s email and his administration’s talks with police behind the scenes were the equivalent to that “Go!” Those words placed them on the wrong side of history. Those words broke a higher law that moved protestors across the Edmund Pettus Bridge, that now moves students to encampments.

Word bridges

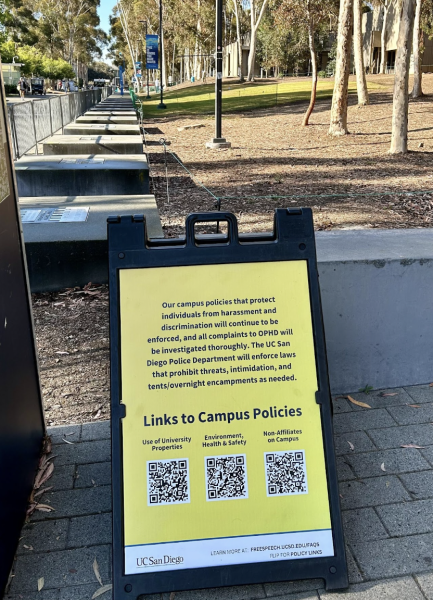

There is a subtext to the Chancellor’s May 5 message and the update which further demonized protestors in the wake of the police brutality. This subtext is revealed in an official sign posted after the encampment was forcefully cleared.

The subtext revealed by this sign is that the encampment was “discriminatory” and that its protestors were harassing individuals in the community. What this sign gestures to, then, is the larger framework that these encampments are being misread within: the frame of antisemitism.

As a way of critiquing this framework, we point to two of the most controversial slogans chanted at encampments:

“From the River to the Sea, Palestine Will be Free!”

“There is Only One Solution, Intifada, Revolution!”

We note, based on our witness, that these slogans were chanted next to others:

“The people united can never be defeated!”

“Your liberation is bound up with mine!”

“We can never be free until we are all free!”

But it is important for us, as teachers, to encounter those words that are characterized as antisemitic.

As teachers, we recognize the ambivalence of the more controversial slogans, the traumas they elicit and the traumas they gesture towards. As one of our Jewish students said, “When my family hears these slogans, they hear a call for the destruction of Israel.” He continued, “But I understand that a Palestinian person hears something completely different: a call for liberation that isn’t necessarily a call to violence.”

His classmate, a Palestinian American, affirmed this. She described the deep-seated Anti-Arab racism that turns her into a monster in the eyes of fellow Americans. She told us of what she sees in her feed: mothers holding their lifeless children, refugees told to flee to sites then bombed. She told us how Anti-Arab racism obscures the meaning of the slogan. For her, it is a call to be acknowledged as human and as dispossessed. It is a call to the same right to exist demanded by her classmate’s mother. Months of peacefully protesting for that demand ended with this student running in tears as police assaulted her friends. “I thought of the people in Rafah running next to bodies,” she said. “The thought of them kept me going.”

Students like these are working through the ambivalence of these slogans. They’re bridging the gap by listening to each other, studying history, and seeing what forces shape their perspectives. The university should be a space where this happens, where perspectives meet, and where tension leads to a deeper understanding rooted in context, fact, and lived experience. It shouldn’t be a space where the charge of antisemitism shuts down dialogue, hides reality, and represses peaceful protest.

Students know this. As another Jewish student told one of us, “My mom says be careful because protestors are antisemitic. I haven’t seen what she sees on the news at all.” He continued, “My roommate is Palestinian. He was pepper sprayed twice at the protests. My mom asked if it was hard to be friends with him. I told her no, not at all.”

We are inspired by such students for cutting through the noise. We see them doing what adult “leaders” cannot do: using words rather than bombs and clubs to move towards a shared future.

We are moved by another type of speech in the classroom that goes beyond slogans: an ecstatic cry for humanity that says, “Why, why, why can’t more people see the wrong of dropping bombs on innocent people, of spending tuition dollars on bombs, of our university’s complicity in warfare and genocide!”

As writing teachers, our classrooms have become the blank page for that cry to be written. Students from Palestine, students with Zionist parents, and students who have no connection to Palestine or Israel are hearing that cry. It is being inscribed deep in their hearts and in ours.

Words that conceal, words that reveal

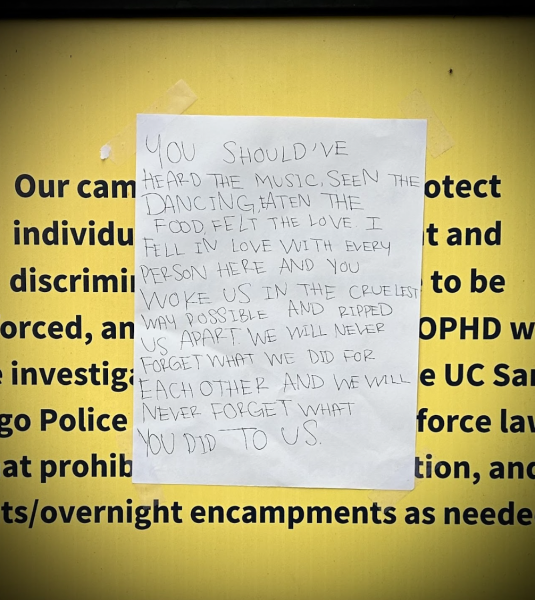

Days after police violently cleared the encampment, that official sign remained on library walk. But something had changed—a revision of sorts.

That is the type of writing we cultivate in our classrooms: words drawn from lived experience rather than from distant observation, writing that invites readers in and reveals the hidden depths.

We praise that writing.

We condemn writing that does violence by concealing the depths.

Writing, like that of the Khosla administration, that criminalizes peaceful protestors and demonizes them in the official record.

Writing that claims to prioritize the safety of the campus but, behind the scenes, invites a small army of militarized riot police to confront our students.

The slick corporate writing of weapons manufacturers and climate killers that lures students to their world-killing work.

Writing, written in shadows, that hides the destructive corporations where student tuition and university endowments are invested.

Writing that erases history while weaponizing historical trauma.

Writing that turns Palestinians into non-people whose lives and deaths are marginal notes in history.

Writing that hides away the Palestinian dead under a rubble of uncontroversial words and obscure bylines.

Words as billy clubs, as bullets, as bombs.

To close, we echo that anonymous writer’s words to those who unleashed violence on our campus:

You woke them in the cruelest way.

You wrote them in the cruelest way.

In solidarity,

Niall Twohig, Lecturer, Warren Writing

Jorge Mariscal, Professor Emeritus Literature/Former Director, TMC Dimensions of Culture

Page duBois, Distinguished Professor, Literature

James Deavenport, Lecturer, Seventh College, Synthesis Writing

Lily Hoang, Interim Director of the MFA in Writing, Professor of Literature

Anna Joy Springer, Associate Professor of Literature/Writing

Amy Sara Carroll, Associate Professor of Literature and Literary Arts

Jac Jemc, Full Teaching Professor of Literature

Luis Martin-Cabrera, Associate Professor of Literature and Latin American Studies

Tina Hyland, Lecturer, Sixth College

Anthony Kim, UCSD Alumni, Literature PhD

Rosiangela Escamilla, Professor at San Diego Mesa College

Lilly Irani, Associate Professor, Communication

Erin Hill, Assistant Professor, Communication

Reece Peck, UCSD Alumni, Communication PhD

Brandon Som, Associate Professor of Literature and Writing

Carolina Montejo, Lecturer, Muir College

Muhammad Yousuf, TA, Dimensions of Culture Program

Chris Perreira, Associate Professor, Ethnic Studies

Matthew Irwin, Lecturer, Sixth College

Ashvin Kini, UCSD Alumni, Literature PhD

Arielle Katzschner, Undergraduate Student

Glen Motil, Library Assistant Manager, Alumni Literature BA and MA

Bayan Abusneineh, Assistant Professor, Women’s, Gender and Sexuality Studies, UCSD Alumni PhD

Theodora Dryer, UCSD Alumni PhD

Elizabeth Sine, UCSD Alumni, History PhD

Zulema Diaz, UCSD Alumni, Literature

Yumi Pak, Associate Professor of Black Studies, UCSD Alumni Literature PhD

Rohan Grover, BS Bioengineering Revelle 2018

Joe Babcock, Adjunct Assistant Professor of English, University of San Diego

Isabelle Yan, UCSD Alumni Class of 2020

Aundrey Jones, Assistant Professor of African American Studies at Lake Forest College

Benjamin Balthaser, UCSD Alumni, Literature PhD 2010

Amy Kennemore, Lecturer, Latin American Studies, UCSD

Simeon Man, Associate Professor of History

Rihan Yeh, Associate Professor, Anthropology

Violeta Sánchez, UCSD Alumni, Professor MiraCosta College

Megan Turner, UCSD Alumni

Mollie Twohig, Caregiver, Relative of UCSD faculty

Melissa Martinez, UCSD Alumni, Professor at Palomar College

Davorn Sisavath, UCSD Alumni, Ethnic Studies PhD

John Rieder, UCSD Alumni, Professor at Southwestern College

Linh Thủy Nguyễn, UCSD Alumna, Ethnic Studies PhD

Tanner Smith, UCSD Alumnus

Erin Cory, UCSD Alumna, Communication PhD

Antonieta Mercado, UCSD Alumnus, Communication

Emma Uriarte, Lecturer, Warren Writing

Clare Rolens, UCSD Alumni, Professor at Palomar College

Josen Diaz, Faculty, University of San Diego

Dillon Chapman, Lecturer, Dimensions of Culture

Disclaimer: These signatories were last updated on June 4. A daily-updated list of co-signers can be found at the bottom of the letter.