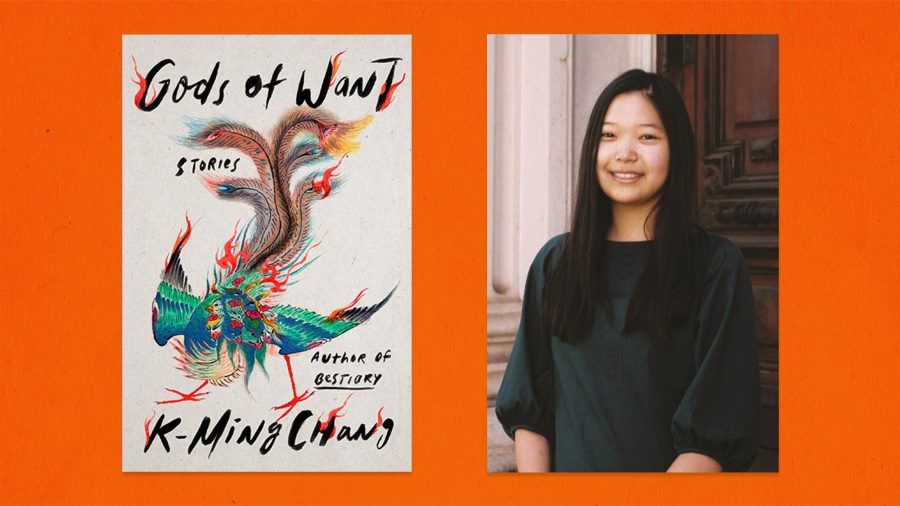

Book Review: “Gods of Want”

Oct 9, 2022

K-Ming Chang is an expert at employing magical realism as a medium for encapsulating the Asian American experience of womanhood, with a frequent emphasis on queerness as a compounded force.

K-Ming Chang made waves in the industry with the arrival of her debut novel, “Bestiary,” published in 2020 when she was just 22 years old. “Bestiary” focuses on a queer Asian girl navigating mystical events beginning to course through her family as she slowly begins to turn into the tiger from a childhood story told by her mother. Chang’s fresh voice and take on this subject matter earned her debut a longlisting for the Center for Fiction First Novel Prize and the PEN/Faulkner Award. The first few chapters served as my introduction to Chang and her visceral descriptive style that incorporates elements intense enough to make the reader uncomfortable. She utilizes such stark bluntness and couples it with images that are both intensely graphic and fantastical.

“Gods of Want ” is a collection of short stories — some of which have appeared in other publications including Nashville Review, Sine Theta Magazine, and Sinister Wisdom — serving as her second publication. The novel is divided into three parts: Mothers, Myths, and Moths, each of which bear her signature finesse of distorting possibility and constructing a world in which absurdities are simply a means of experiencing life. There is a reason behind this division. The stories that compose Mothers deal with familial ties and obligations, the emphasis within Myths is placed on love, and Moths tackles the interconnectedness of spirits, time, and want. Thematically, the intersectionality of womanhood, Asian American identity, and queerness are all hyperpresent throughout the novel, and they are particularly powerful because it is clear that the exploration of these identities comes from someone who experiences them firsthand.

Discussing Chang’s work is drastically different than experiencing it. It’s vivid and raw. For example, in “Mariela” within Moths, the narrator talks about a young girl from her childhood, Mariela, as the two girls grew up intertwined. After school one day, they decided to play a game that consisted of naming their favorite bodily feature of the other and keeping it for themselves. Mariela chooses the narrator’s eyelashes and the narrator proceeds to “[close] her fingers on the fringe of [her] lashes and [tugs] until it tore away, [her] eye lining itself in blood.” Chang doubles down on the tension when the narrator chooses Mariela’s teeth. Images like this are a constant for Chang; nobody else seems to consolidate intensity like her, and nobody seems to run with fiction in the way that she does.

Chang has received a fair amount of criticism for her writing style which appears to be fluid rather than solid. Lacking a particular focus and instead constantly shifting, her writing style can become an issue when readers attempt to attach themselves to her characters. Personally, this criticism does not resonate with me because I applaud Chang’s success in undermining conventional standards. It serves as a reminder that art has no form and can exist in malleable spaces. Digesting a story in its entirety is also a necessity for “Gods of Want,” as the journey sways and bends but arrives holistically at its end, fully formed with the emotional weight Chang means to express. My critique of Chang differs from the ones I have most commonly seen; instead, I take note of her portrayal of immigrant parents.

Many of the stories within the novel involve characters and their relationship with their parents, most prominently mothers and daughters. Chang beautifully encapsulates what it means to be a daughter: the pain, desire, and strength that they are born knowing. It is a complicated relationship, a dichotomy of individuals burdened and gifted with the boundless perception of one other. However, I frequently found that she portrays mothers and elders in an almost animalistic way. Their superstitions are so incredibly extreme that they seem inhuman. While I understand this serves a purpose in portraying the mythical elements of the Asian experience, it also can also paint superstition in a poor light and make these people creatures instead of humans. ‘Mariela’ displays some of this imagery in which Mariela once found her mother scooping her cremated brother into her mouth from off of their bathroom floor. It’s a visceral display of grief — and part of what makes Chang’s work so enticing — but I think there’s a claim to be made about the negative effect these images can hold, especially when portraying people of color.

Chang’s work, however, ultimately does more good than anything else. She sheds light on the Asian identity, queerness, and feminity that overlap repeatedly. “Homophone,” a personal favorite of mine, is a paramount example of all of these things colliding. It briefly chronicles the romantic relationship between two Asian women and gives them rich depth over the course of a few pages. She is whip-smart at expressing the demands of culture and the way the world attempts to mold women. Representation alone is a powerful resource, but Chang’s pen transcends this by making her characters matter more than anything else at any given moment.

“Gods of Want” has been one of my favorite releases of the year. My favorite stories include “Auntland,” “Nine-Headed Birds,” “Homophone,” and “Resident Aliens.” The novel is devastating, insightful, and gripping. It hurts and it holds, but it forces you to reflect. While I love this book and recommend it highly, I can only do so with caution. It can be intense and draining, especially if you align with the identities that she emphasizes, but the connectedness that it offers exceeds the pain.

Released: July 12, 2022

Grade: A

Image courtesy of Shondaland