Juana Segura

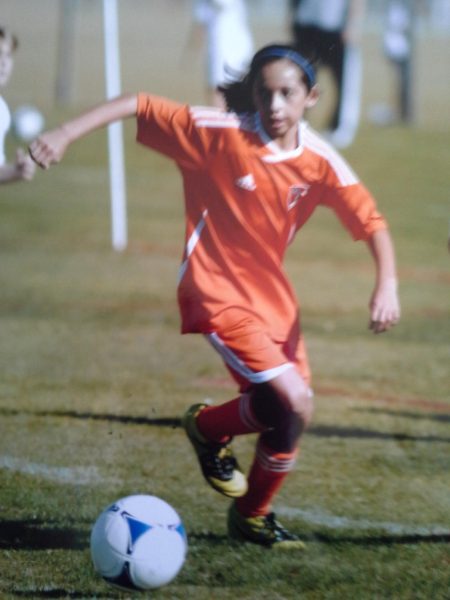

From a very young age, I was sure that all I wanted to do with my life was play soccer. I began playing at the age of three and fell in love with the sport before I even knew who I was. It was easy to shape my identity and my existence around it. I wore sparkly soccer-themed clothes from Justice and kept a mini soccer ball with me at all times. Playing soccer taught me more about myself than school ever did, and I grew up confident and secure in myself as a result. It made me feel like I was actually worth something.

However, when I officially quit competitive soccer as a teenager, that was no longer the case — soccer had become a source of anxiety. Since then, I have constantly asked myself: What do I do now that an entire part of my identity is no longer part of me? Quitting soccer was like going through the worst imaginable breakup with the love of my life.

When I was 13, at the peak of my soccer career, it seemed as though I was on track to achieving my dream. I was playing for a Developmental Academy league, which not only meant I’d be playing nationally but also that I could be recruited by colleges. My entire family was betting on that future scholarship, telling everybody that I would be playing on the U.S. national team. But my experience at the DA would very quickly take a plunge.

Looking back, I’m compelled to share everything that happened — everything that made me hate soccer in those three years. I’m tempted to spit out every insult I can muster at the DA coaches, the girls I competed against, my well-intentioned high-pressure family, and especially at myself. At an age when my insecurities were on full display and my self-image was so malleable, soccer became a toxic boyfriend-adjacent figure, insistent on me hating myself. Every mistake I made, every wrong pass, every missed shot, was grounds for ruthless berating. I knew that with every bad game, I wasn’t just upsetting my coaches; I was disappointing my parents who put in so much money and time into extra training. My entire self-worth was based on me being good at this sport, and when I came to the harsh realization that I was not valued in that league, it was enough to break me.

To this day, I’m not entirely sure why I quit soccer. People assume different things; some think it was my parents pushing me too hard. This isn’t entirely true — while they were intense in their own way, they never fully understood the severity of the pressure I was under. Alternatively, my friends who were on that DA team with me would say that it was because of the coaches and the extremely unhealthy environment that festered within the team. This is probably more accurate since they knew firsthand how bad it was.

The only thing I am certain of is that I don’t regret quitting the DA. Quitting that club meant that I could get my life back and enjoy soccer in a different, less stressful setting. I finished out my high school career as captain of our varsity team, surrounded by girls and coaches who genuinely valued me. Soccer went from being a toxic boyfriend to being the old partner I knew and loved — one that supported me, helped me feel in control, and connected me to myself.

But, because I quit the DA, college soccer was no longer an option for me. I watch my friends from home play college club soccer and still slightly regret my decision. Nothing will ever replace the feeling of being on the field, adrenaline coursing through my body, analyzing the game and knowing that I was in control. I miss that feeling. I crave it constantly. I love soccer passionately — I always have, and I always will.

There are plenty of regrets and reliefs I have surrounding soccer. In the past four years, I’ve been desperate for my family and friends to understand how I feel about the sport; I’ve been desperate to understand those feelings myself. How can I explain how much I miss soccer, yet simultaneously not regret quitting? I’m old enough to understand that the reason I quit soccer was nowhere near my fault or even my parents’ fault. But I think what I’ve come to realize is that this isn’t something that others need to understand, so long as they trust I made the right decision. I’ll hold onto these reflections until I’m ready to say goodbye.